Anna Akhmatova’s Poems against Terror, Part 1

Anna Akhmatova, a renowned poet before the October Revolution, became an ostracised outsider in the Bolshevik state. This is also reflected in her poems. Opening of a three-part series on the poet.

At night, fear rummages through my belongings,

a hatchet flashes in the moonlight.

Behind the wall, an ominous rustling:

Rats? A ghost? A thief?

In the kitchen haze a numbers game

of creaking planks and dripping water.

Outside the window a stealthy scurry,

a black beard flashing past the window.

Match fragments, candle stubs –

you will never catch a ghost.

I’d rather choose muzzle flashes,

the cold hand of the gun on my chest!

I’d rather mount the scaffold openly

on the great square, cheered and bewailed,

and quench the thirst of the earth

proudly with my blood.

From my fear-soaked sheets a paralysing breath

of pestilence blows to my head.

Silently the cross beseeches on my breast:

Lord, breathe peace into my heart!

Anna Akhmatova: poem no. 25 (1921); from: Anno Domini MCMXXI (1922); English adaptation

Sheltered Childhood and Youth

When in 1889 Anna Akhmatova – as Anna Gorenko – was born in a village near Odessa, she seemed to be destined for a life in sheltered and orderly ways. Both her parents came from privileged backgrounds: Her father, a Ukrainian from a Cossack noble family, served as an engineer in the navy. Her mother was a Russian noblewoman with family connections to Kiev.

Indeed, Akhmatova’s life initially took the course that was to be expected for a girl from her social milieu. After the family moved to Tsarskoye Selo near Saint Petersburg in 1890, she received there her secondary education. In the summer, the family used to retreat to a dacha near Sevastopol in the Crimea.

After her parents separated in 1905, Akhmatova moved completely to the Crimea with her mother and siblings for a time. Shortly afterwards, she finished her school education in Kiev and then began to study law there – in a reduced programme for women. In 1910 she married the poet Nikolai Gumilyov and travelled with him through Europe. Two years later, a son was born to the couple – Lev remained Akhmatova’s only child.

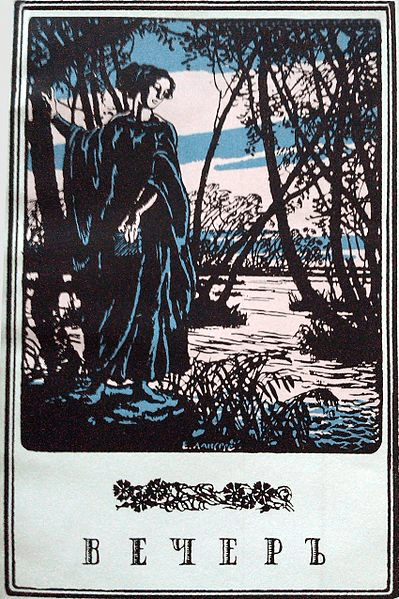

Akhmatova also quickly became successful with her poetry. Her father, though, distrusted her artistic talent, which is why she published her poems not under her family name, but under that of her Bulgarian great-grandfather. By contrast, the literary world received her poems with great favour. Her first two volumes of poetry, published in 1912 and 1914, met with broad recognition.

Promising Beginning as a Poet

Soon Akhmatova established herself in artistic circles. Together with her husband, Osip Mandelstam and others, she formed the Цех поэтов (Tsech Poetow), a poetry workshop dedicated to a style that was more representational than other poetry of the time and more oriented towards everyday life.

In Russian literary history, the poetry in question is called „acmeist“. The Greek root of the word (akme: climax, peak, maturity) points to the special appreciation for this poetry and for the epoch as a whole in which it was written. This is also reflected in the labelling of the period from 1890 to 1930 as the „Silver Age“ – in distinction to the Golden Age, characterised by poets such as Pushkin, Lermontov and Gogol, which is located in the first half of the 19th century.

Acmeism turned against the prevailing, symbolist-hermetic style, although without entering into ideologically hostile competition with it. Thus, one of the most important representatives of Russian Symbolism, Alexander Blok, was a close friend of Akhmatova.

The Turning Point of the October Revolution

The years until the First World War were all in all a happy time for Akhmatova. The war, however, changed her life fundamentally – not only through the events of the war itself, but also and above all as a result of the Bolsheviks‘ subsequent seizure of power.

Poems like Akhmatova’s no longer had a place in the „proletarskaya kultura“ („Proletkult“ for short) proclaimed by the new regime. Already as a member of the despised bourgeoisie, she was generally suspicious. But with her poems, in which personal feelings played a major role, she was also considered an enemy of the people in the cultural ideological sense, an author whose work ran counter to the desired celebration of the new socialist everyday life.

First a Celebrated Poet, Then an Enemy of the State

This was the beginning of a long period of suffering for Akhmatova, which ultimately lasted until her death in 1966. Her poems were banned, and distribution by samizdat – i.e. by copying them secretely, without official permission – was also dangerous.

This was all the more true in view of the increasing aggressiveness of Soviet cultural policy under Stalin. Some of Akhmatova’s poems only survived because friends learned them by heart and passed them on orally to others.

In addition, Akhmatova’s husband, from whom she had divorced in 1918, was suspected of counter-revolutionary activities and was shot in 1921. As a result, the poet herself and her son also came into the sights of the authorities and were observed at every turn. The feeling of threat that arose from this was expressed by Akhmatova in the poem reproduced above.

Images: Kuuma Petrov-Vodkin (1878 – 1939): Anna Akhmatowa (1922); St. Petersburg, Russian Museum; Anna Akhmatova (1904); : Cover of Akhmatova’s first book of poems (Vyecher/Evening), designed by Eugène Lanceray (1912);Anna Akhmatova with her first husband, Nikolai Gumilyov, and her son Lev, 1915; photo by L. Gorodetsky (all pictures from Wikimedia Commons)

Hinterlasse einen Kommentar