Anna Akhmatova’s Poems against Terror, Part 3

The concern for her imprisoned son and the struggle for his survival were an extreme psychological and physical burden for Anna Akhmatova. At times, even the thought of death seemed like salvation.

To Death

You will come anyway – so why not now?

I am waiting for you, my life is too burdened.

The door is wide open and the light is extinguished

for you, the undemanding stranger.

Appear to me in whichever shape you like!

Tear my heart apart with a poisoned dart,

sneak up like a cunning thief

with a heavy piece of wood,

wrap me in typhoid smoke

suffocate me with a boring fairy tale,

until the pale-faced caretaker

and the blue-capped commissioners pick me up.

That’s all the same to me. With the mists

dancing on the Yenisei, the shining Polar Star

and the blue sparkle in beloved eyes

my last fear has dissipated.

Anna Achmatowa: K Smyerti (1939); Poem no. VIII; from the cycle Реквием (Requiem; 1934 – 1963); English adaptation

Death as a Bitter Reality for Akhmatova’s Fellow Poets

Subjective Poetry and the Dignity of the Individual

Committed Compassion: Giving a Voice to the Victims of Terror

Compassionate Poetry: Incompatible with Marxist Doctrine?

When the Utopia of a More Just Society Solidifies into Dogma

Alienation from Former Ideals as a Motivation for Persecution

Death as Salvation?

During the Stalinist Purges, Anna Akhmatova’s son Lev was, like many others, imprisoned. Since his father had been executed as a supposed counter-revolutionary, he was considered to be suspicious quasi by nature.

Akhmatova had to wait in queues outside the prison for hours to bring her son something to eat or warm clothes. Given the harsh prison conditions, she always had to be prepared for her son to die. Execution was also possible at any time.

In her cycle Requiem, the poet dealt with the extraordinary burden this meant for her and her son, but also for other people affected by persecution. In a poem of the cycle, reproduced above, she even plays with the thought of escaping into death in view of her psychological and physical exhaustion. However, in keeping with her unpretentious style, avoiding any pathos, she distances herself from her own despair here with subtle irony.

Death as a Bitter Reality for Akhmatova’s Fellow Poets

What for Anna Akhmatova was only a mind game became bitter reality for other poets of her time. Many saw themselves so marginalised by the Bolshevik rulers or were so relentlessly persecuted that they either died of debilitation or took their own lives.

Alexander Blok died as early as 1921 from inflammation of the heart, which had become life-threatening due to his acute malnutrition. The poet had a particularly close relationship with Akhmatova, to whom he referred in several poems. Blok also plays an important role in Akhmatova’s poetry, both in terms of stylistic orientation and – as in her poem Гость (Gost‘ – The Guest) from 1914 – as a person.

Osip Mandelstam, who had collaborated with Akhmatova in the Acmeist poetry workshop from before the October Revolution, was targeted by the regime from 1934 onwards because of disliked publications. When the Stalinist authorities briefly let him go in 1937, he and his wife spent some time with Akhmatova in Leningrad.

The poem she wrote for him during this time (Немного географии / Nyemnogo geografii: A Little Geography) turned out to be a requiem. Mandelstam did not survive the renewed camp imprisonment that followed shortly afterwards. At the end of 1938, he died, physically and psychologically shattered, in a camp in Vladivostok.

Mandelstam had already attempted suicide, Akhmatova had only toyed with this possibility. Sergei Yesenin and Marina Tsvetayeva, however, actually took their own lives: the latter in 1941, Yesenin as early as 1925.

Subjective Poetry and the Dignity of the Individual

All these poets have developed their own distinctive style. What unites them, however, is the insistence on the independence of the individual, on its autonomous interpretation of the world. This was reflected in a primacy of subjective feeling and in its poetic shaping.

Of course, it can be argued that the authors thus inevitably placed themselves in opposition to the official communist doctrine. After all, it is precisely the crucial characteristic of the latter that it strives for an objective change of the course of history. In this context, the focus on subjective feelings seems not only superfluous, but even obstructive. It is seen as a bourgeois escapism, through which the struggle for a more just society is weakened.

Committed Compassion: Giving a Voice to the Victims of Terror

On the other hand, the primacy of the individual also implies that every single human being is respected in its uniqueness and dignity. Sensitive poetry, such as that written by Akhmatova and her fellow poets in the first half of the 20th century, therefore always included empathy with others.

For Akhmatova’s poetry in particular, sympathy and compassion were essential. In the epilogue to her Requiem cycle, she explicitly points to this deeply felt solidarity with others as a central motivation for her writing. With her poems, she wanted to rescue from oblivion those who, like her and her relatives, had been caught up in the wheels of history. In this way, a voice could be given to those who had been reduced to silence:

How I would have liked to mention all their names!

But the wind has blown them away, the lists are burnt.

For them, from their unhappy words

this blanket of verses is woven.

They will live on in my spirit,

even if new misfortunes come my way.

Even if they take the voice from my mouth,

its suffering will sing of all the other sufferings.

Compassionate Poetry: Incompatible with Marxist Doctrine?

Of course, a cycle of poems such as Akhmatova’s Requiem, dedicated to the victims of Stalinism, could not be printed under the Stalinist dictatorship – the text was not published in the Soviet Union for the first time until 1987. Nevertheless, Akhmatova’s poems demonstrate that the condemnation of a subjective approach to poetry by the socialist cultural doctrine cannot necessarily be derived from the ideal of communism.

Isn’t active compassion for others the very root of communism – the very motivation for the development of the utopia of a more just society in which hunger and need are overcome?

It is true that this does not correspond to Marxist theory. As is well known, the latter assumes that it is not consciousness that determines being, but being that determines consciousness – that is, that the decisive change does not take place on the level of subjective reflection, but on the level of an objective structural change.

Ultimately, though, we are dealing here with a chicken-and-egg problem. Marx himself is the best example of the fact that a change of consciousness on the level of individual subjects is needed to initiate social changes – which in turn can promote a change of consciousness in others and thus trigger a comprehensive structural change.

The initial change of consciousness in individuals, however, is inextricably linked to emotional components. It is based on compassion for those who suffer from oppression and disadvantage, who are marginalised or excluded from social participation altogether.

When the Utopia of a More Just Society Solidifies into Dogma

Seen in this light, the hatred with which sensitive-compassionate poetry was persecuted in real-socialist societies is basically a case for the psychiatrist. The blanket condemnation of such poetry as „bourgeois“ and „decadent“ ultimately testifies to an alienation of cultural functionaries from the ideals that stood at the beginning of the struggle for social change.

Due to this alienation, all that remains of the ideal is its outer shell. Thus, the ideal congeals into a dogma that is only enforced for its own sake. The increase in justice and humanity that was originally associated with it no longer plays any role at all.

Alienation from Former Ideals as a Motivation for Persecution

The persecution of authors in whose work the original communist ideal of practical empathy and compassion for others – as a prerequisite of a common struggle for a better world – lives on, could then be explained psychoanalytically with a shift mechanism.

Instead of taking a self-critical look at one’s own behaviour and correcting mistakes, those in which the lost ideal is reflected are persecuted. They are the mirror of one’s own past, supposed to be destroyed in order to escape the painful process of coming to terms with one’s own aberration. The degree of aggression emerging in this is at the same time a yardstick for the degree of alienation from one’s own ideals.

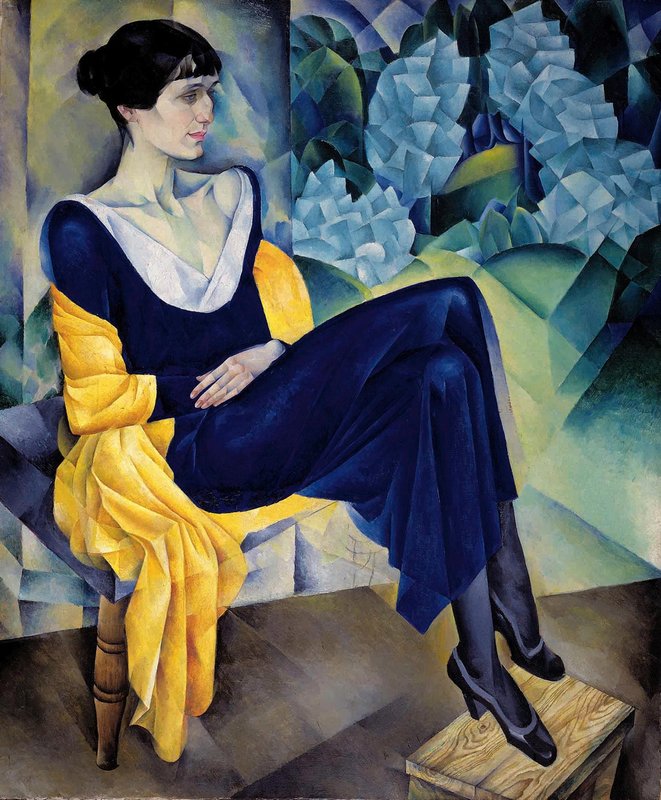

Image: Nathan Altman (1889 – 1970): Portrait of Anna Akhmatova (1914); Saint Petersburg, Russian Museum; Wikimedia Commons

Hinterlasse einen Kommentar