Start of a Five-Part Series with Poems by Jacques Prévert

For the French poet Jacques Prévert, school was – also from his own experience – more of an obstacle than a catalyst for the free spirit. His poems therefore repeatedly call for turning away from the traditional understanding of education.

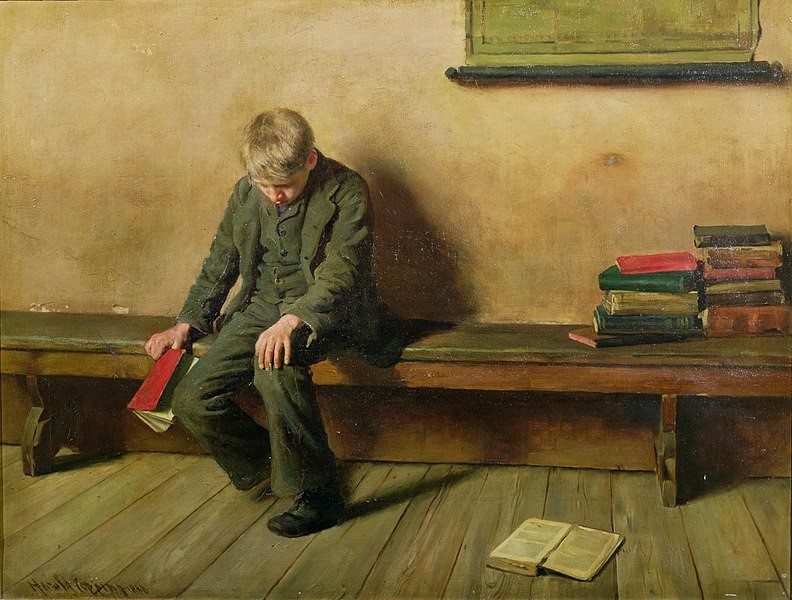

The Dunce

Below him

the parted heads

of the model students,

in front of him

the lurking gaze

of the teacher.

The fusillades of questions

rain down on him,

he staggers

in the hail of bullets of problems

that are not his own.

But suddenly

the bright madness laughs

through his gloomy face.

He reaches for the sponge

and simply wipes it away,

the labyrinth of facts and figures,

of data and terms,

of phrases and formulas,

and under the cheering of the class arena

he paints over in rainbow colours

the dark board of unhappiness

with the radiant face of happiness.

Jacques Prévert: Le cancr from: Paroles (1946)

Prévert’s Difficult Childhood

Looking at the biography of the French poet Jacques Prévert (1900 – 1977), some might be inclined to say that this author did not exactly imbibe poetry with his mother’s milk.

Prévert’s father had to eke out a living with odd jobs for a long time before he finally found work with a charity association in Paris [1]. In the jungle of the big city, the son fell into the petty crime milieu, so that Prévert himself later wondered about the „virginity“ of his criminal record [2]. In all this, school was nothing more than an annoying evil, and skipping lessons consequently led to leaving school as early as possible (at the age of 15).

Critical View of Traditional School Education

If someone had asked Prévert how he could become a poet with this limited formal education, the answer would probably have been that this had happened not despite, but rather because of his distance from the school system. Thus, for example, he argued against the standardisation of intellectual progress that lockstep learning in school entails.

According to Prévert, to say that a child does not progress in school often overlooks the other developments that a child undergoes, which are not measured by school tests and may not even be related to instruction [3]. With the French philosopher Montaigne, Prévert therefore criticizes the „imprisonment“ of the child’s mind in school, where it is at the mercy of the whims of a bad-tempered teacher and thus deprived of its individual potential [4].

With the Bird of Imagination against Intellectual Paternalism

In Le cancre – the poem reproduced above –, a pupil rebels against the mental oppression by wiping away all the abstract facts and figures he is supposed to learn from the blackboard and painting them over with the „face of happiness“.

Analogously, in Page d’écriture (Task Sheet), the conditions for mental freedom are created precisely by the fact that the pupils turn away from the teacher’s repetition exercises and devoting themselves to the bird of imagination, whose song causes the walls of the classroom – and thus the school reality – to collapse:

Arithmetic Exercise

Two plus two makes four

plus four makes eight

which makes the same

when multiplied by two

minus four makes four again

a tightly woven arithmetic chain

round the numbers round the heads

on accurately demarcated squares

suddenly

out of the blue

a trembling feather

a bird’s feather in front of the window

gliding past the classroom

gliding into the hearts

an unpredictable song

breaking the tightly woven chain

round the numbers round the heads

into countless spiritual sparks

a sea of colourful marbles

incalculably glittering

freed

the pencil dives into it.

And the numbers turn into objects again

the glass panes turn into sand

the ink turns into water

the desks turn back into trees

the chalk becomes a chalk rock

and the pencil a bird [5].

The „Unchained“ Child as a Public Nuisance

Another poem by Prévert about childhood and traditional education is Chasse à l’enfant (Child Hunt / Hunt for the Child). It is based on a true incident – the uprising against the violence of the guards and the subsequent escape of inmates from a Breton reformatory for minors in 1934. For those who helped to apprehend one of the fugitives, a reward of 20 francs was offered.

Prévert takes up the incident in his poem from the perspective of a child on the run. Like a „hounded animal“, it is chased by the „pack of decent people“, who perceive its escape to freedom as an attack on the social order and seek to punish it accordingly. The fact that the reference is not to just any child, but to „the“ child in general elevates the unbound, untamed child to a symbol of the intellectual freedom suppressed in everyday life in bourgeois society.

The poem thus describes the child’s attempt to escape as an example of the self-assertion of the human spirit, beginning with its resistance against its suppressive moulding at school. In other words, intellectual freedom is only possible in the long term if the spirit’s wings are helped to unfold instead of being clipped at school.

Child Hunt

On their wings, the seagulls

playfully catch the sparkling light

that dabs the waves

around the island with stars.

All of a sudden, shouts resound like gunshots:

„Rascal! Hooligan! Deadbeat! Scoundrel!“

It’s the pack of decent people,

dutifully chasing the unbound child.

Like a wounded animal

the child strays through the gloomy night,

while behind him the cries

of the decent people resound:

„Rascal! Hooligan! Deadbeat! Scoundrel!“

Nobody needs a hunting licence

for hunting the child. The freedom of hunters

stands above the freedom of the child,

who flees through the gloomy night.

„Rascal! Hooligan! Deadbeat! Scoundrel!“

The arms of the moon reach ghostly

between the night-pale waves

into which you plunge your unbound arms.

Will you reach the shore? [6]

References

[1] On the occasion of the 40th anniversary of Prévert’s death in 2017, several monographs on the author and his work were published, including biographically oriented appreciations of his work (cf., among others, Aurouet, Carole: Jacques Prévert. Une vie. Paris 2017: Les Nouvelles Éditions JMP; Hamon, Hervé: Prévert, l’irréductible. Tentative d’un portrait. Paris 2017: Lienart). Another detailed study on Prévert dates from 2021 (Perrigault, Laurence: Prévert. Paris 2021: Les Pérégrines, Collection Icones).

[2] Cf. Prévert’s statement in an interview with André Pozner: Prévert/Pozner: Hebdromadaires (1972), S. 85. Paris 1982: Gallimard.

[3] „Un enfant, (…) à l’école, on dit: il ne fait pas de progrès. Pourtant, on ne sait pas, on ne peut pas savoir s’il n’en fait pas, dans une direction différente“ – „Often a child at school is accused of not making progress. But the truth is that we cannot know that at all. Perhaps the child is making progress, only in a completely different direction“ (ibid., p. 101).

[4] Ibid., p. 101 f.

[5] Cf.Prévert: Page d’écriture; from: Paroles (1946), p. 146 f.

[6] Cf.Prévert: Chasse à l’enfant (PDF); from: Paroles (1946), p. 86 f. Song version by Les Fréres Jacques (1957).

Harold Copping (1863 – 1932): The Dunce (1886); Bournemouth, Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum (Wikimedia Commons); Photo of Jacques Prévert (1920s); photographer unknown; Paris, Musée Carnavalet

Hinterlasse einen Kommentar