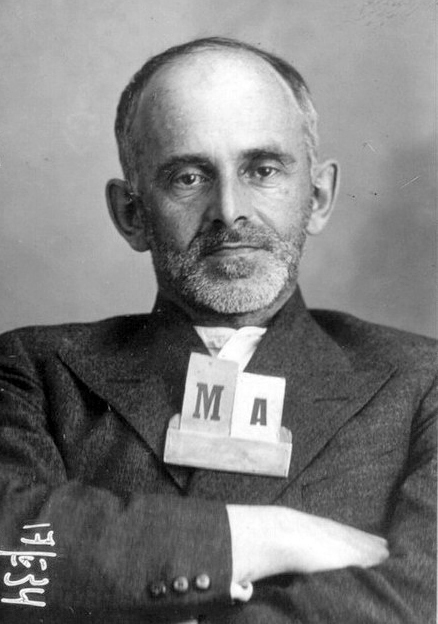

A Poem Based on Ossip Mandelstam’s Stalin Epigram

In 1933, Osip Mandelstam wrote a poem against Stalin, which he ultimately had to pay for with his life. In an adapted form, the poem can also be applied to autocratic rulers in general – not least the current Kremlin despot.

We step silently, without feeling our steps.

The wind blows away our words,

the meagre crumbs of our talks,

shadowed by HIM, the Kremlin giant.

His fingers shine as slippery as worms,

heavy as a judgment weighs his word.

Vermin crowd around him, eager to obey,

reverently bowing down to the shaft of his boot.

Beneath him the crooked necks of his subordinates,

half shrunk to animals due to their subjugation.

Some whistle, others meow or howl,

HE alone gives orders as he barks,

a prince of hell who incessantly forges decrees,

decrees that strike you down like projectiles.

And every torture rack is a resting place for him,

a raspberry-sweet bloodbath for the giant leader.

Based on Osip Mandelstam: Мы живем, под собою не чуя страны… (1933)

A Terrible Euphemism

Chistka – Purges. This term is used to describe an epoch in Soviet history in the 1930s.

It is one of the most terrible euphemisms in historiography. For in concrete terms, „Chistka“ means here: Cleansing the regime of opponents. Several million people lost their lives because they were classified as opponents of the regime by Stalin and his secret service henchmen. Between 1936 and 1938 alone – the time of the so-called „Great Terror“ – around a thousand people were executed every day as supposed enemies of the people.

To be classified as an opponent of the regime, one did not have to be an anti-communist by any means. It was enough to hold a dissenting opinion to the official doctrine of communism.

You also didn’t have to be in open opposition to the regime to be considered anti-regime. It was enough to know someone who had been classified by the secret service as an unreliable citizen. It was enough to write poems that did not fit into the corset of the official cultural ideology. It was even enough to distribute such poems – of course under the table, and mostly orally, in whispers, because printing works that did not conform to the state was, needless to say, out of the question.

Mandelstam’s Survival as a Poet Thanks to Powerful Patrons

It was against this background that Osip Mandelstam wrote those verses in 1933 that later went down in history as the „Stalin Epigram“. Mandelstam – born in 1891 in Warsaw, then part of Russia, as the son of a Jewish leather merchant – was one of those authors whose work contradicted the officially proclaimed „proletarnaja kultura“ (abbreviated to „Proletkult“), especially with his early poetry, which was close to Symbolism. Nevertheless, unlike most other poets who did not submit to the dictates of the socialist cultural doctrine, he was not completely banned from writing and publishing.

The reason for this was primarily that in the 1920s Mandelstam concentrated more on writing essays and other forms of prose. Even more important was that he could count on the support of the powerful editor-in-chief of the newspaper Izvestia and chairman of the Comintern, Nikolay Bukharin.

Nevertheless, writing a work critical of Stalin in the extremely repressive phase of the 1930s was a life-threatening undertaking for him too. Mandelstam himself, of course, was also aware of this. The verses therefore circulated exclusively orally among the poet’s closest circle of friends.

A Life-threatening Poem

However, it was a key feature of the Stalinist dictatorship that the secret service had its ears everywhere. No one could be sure whether what they said to someone else in confidence would not end up in the files of the state security organs in a roundabout way.

Precisely this is what happened to Mandelstam’s poem. Only six months after it was written, he was arrested and confronted with a handwritten version of his epigram – one of his supposed friends had passed it on to the secret service.

After intensive interrogations, presumably involving torture, Mandelstam was not sentenced to death, though – as was to be expected after a text openly critical of Stalin –, but only sent into exile in the Urals and later to Voronezh on the Volga. Once again, this was thanks to Bukharin’s intercession, this time reinforced by further supporters such as Boris Pasternak, the later creator of „Doctor Zhivago“, and other public figures.

Mandelstam was apparently protected by his reputation as an author, which would have made his assassination an image problem for the regime. In retrospect, however, the question arises whether this was an advantage for the poet. For instead of the quick bullet, Mandelstam was condemned to a death by instalments.

The torture suffered during the interrogations already burdened him so much that he attempted suicide in exile. When he was arrested again in 1938 – his supporter Bukharin had himself been declared an enemy of the state and executed in the meantime –, he did not survive the renewed tortures and died in a Gulag camp in Vladivostok at the end of the year.

About the Adaptation of the Poem Presented Here

Mandelstam’s „Stalin Epigram“ does not directly mention the dictator’s name at any point. However, some attributes of the ruler alluded to in the verses establish an unequivocal reference to Stalin.

This is especially true of the impressive moustache, a trademark of this Soviet leader, and the autocrat’s designation as „Ossetian“. For it was precisely this ethnic group – whose main settlement area is today de jure divided between Russia and Georgia, but de facto also controlled by Russia in the south – that Stalin belonged to.

These references to Stalin – unspoken but immediately comprehensible to everyone – were important at the time in order to give the poem a concrete political meaning. Today, by contrast, they impede the unfolding of a meaning that goes beyond the time of the poem’s composition.

However, such a supra-temporal meaning is inherent in the poem itself. The autocratic patterns of rule implied in it are not, after all, specific to Stalin’s reign. Rather, they can also be observed in other authoritarian regimes – like for example in the one established by the current despot in the Kremlin and his counterparts in Washington or Beijing.

For this reason, the references pointing directly to Stalin have been deliberately omitted in the adaptation of the poem presented here. In other respects, too, the emphasis was not on the closest possible literal transcription, but on a contemporary garment for the spirit of the poem. This approach also appears to be justified by the fact that translations closer to the original already exist.

Images: Osip/Ossip Mandelstam 1914 und 1934 ( Photo taken after his first arrest); Collage with AI-generated pics from Wolfgang Eckert and Andreas Volz (Pixabay)

Hinterlasse eine Antwort zu Der Diktator – rotherbaron Antwort abbrechen